Buy This Magazine Or The Dog Gets It

click to enlarge

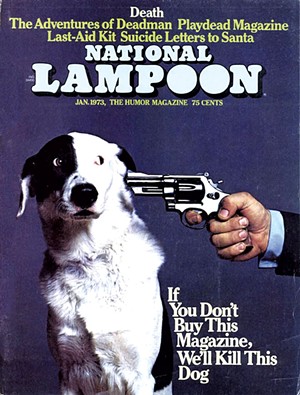

The cover of the January 1973 issue of National Lampoon, the groundbreaking humor magazine's Death issue, depicts a handsome black-and-white dog against a blue background. To the right, the meaty hand of an unseen assailant holds a handgun to the side of the dog's head at point-blank range. The collarless mutt's body language, especially the way he side-eyes the gun, gives the uncanny impression that he's aware of the imminent danger. A caption reads: "If You Don't Buy This Magazine, We'll Kill This Dog."

The cover is a pop-culture touchstone, recognizable even to people who know the National Lampoon only from Animal House or the National Lampoon's Vacation movies. Designed by the late Lampoon art director Michael Gross, the cover is widely regarded as one of the greatest not only in the history of the magazine but in the history of magazines, period. In 2005, the American Society of Magazine Editors named the Death cover one of the Top 40 Magazine Covers of the Last 40 Years. It ranked No. 7, right between the New Yorker's 9/11 cover on September 24, 2001 and the October 1966 cover of Esquire. The latter touted John Sack's 33,000-word story on the Vietnam War, a benchmark piece in the nascent New Journalism movement.

The content of the January '73 National Lampoon couldn't compete in seriousness or importance with that of its neighbors on the ASME list: The cover teases inside features called "Last-Aid Kit" and "Suicide Letters to Santa." But the Death issue would nonetheless become shrouded in darkness.

The following month's National Lampoon featured an inside photo of the dog, Mr. Cheeseface, lying motionless on the floor of an office surrounded by the magazine's staffers. The implication was that the previous issue hadn't sold enough copies to keep the magazine's editors from following through on their threat. It was, of course, a gag: A newsroom full of comedy writers didn't shoot the dog. But three years later, in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, someone did.

The sad tale of Mr. Cheeseface has since become both famous and controversial. The shooting is mentioned in Josh Karp's 2006 book A Futile and Stupid Gesture: How Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever, the original cover of which features an illustrated play on the Death cover, with Mr. Cheeseface holding a gun to magazine cofounder Kenney's head.

Mr. Cheeseface's untimely passing has inspired whispers of conspiracy in certain corners of the internet, including several Reddit threads. The dog is a staple of pulpy online lists of celeb animals that died under mysterious or unusual circumstances, alongside the likes of Budweiser spokesdog Spuds MacKenzie, Tweet the Giraffe from the old Toys "R" Us commercials, and Keiko, the whale in the Free Willy movies.

Though variations exist, the stories about Mr. Cheeseface all suggest murder most foul: that a gunman, perhaps seeking fame, tracked the dog to a farm in rural Vermont and assassinated him. According to Vermonter Jimmy De Pierro, though, that tale is far-fetched.

"It's all bullshit," he said in an August interview with Seven Days.

De Pierro has reason to know: He raised Mr. Cheeseface from a puppy and owned him until the dog's death in 1976. Rumors of the dog's demise have been greatly exaggerated, he said. Yes, Cheeseface was shot and killed in Vermont. But the real circumstances surrounding his death are even stranger than the stories that have been invented about him.

De Pierro, 72, spoke with Seven Days at the West Burke farmhouse of his brother, Mark — who was also present, along with Jimmy's ex-wife, Kathy Daye.

click to enlarge

- Dan Bolles

- From left: Jimmy De Pierro, Kathy Daye and Mark De Pierro

De Pierro currently lives in a cabin on Mark's land. Born in New York, he lived during the 1980s and '90s in and around Montpelier, where he raised a family with Daye, then Kathy De Pierro. From 1984 to 2000, De Pierro operated an Italian ice pushcart in the capital city and occasionally in Burlington — hence his nickname, "Jimmy the Iceman."

In fact, De Pierro used that moniker to run for Vermont secretary of state as a member of the Grassroots Party in 1996. The party, which is no longer active in Vermont, held its meetings at Jimmy's Rack N Roll, the Montpelier pool hall De Pierro owned at the time.

After 42 years, De Pierro believes it's finally time to set the record straight about Mr. Cheeseface's death, as well as the dog's unusual life. Before he began spinning those tales, however, he offered a few words of caution.

"I'm gonna talk your ear off. I digress a lot," he warned, "and I'm probably gonna cry."

Little Friend

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Mark De Pierro

De Pierro is indeed a talker, prone to sometimes-befuddling tangents delivered in a rich Brooklyn accent. And, yes, even after four decades, he still chokes up while reminiscing about his beloved Mr. Cheeseface. De Pierro, who sports a bushy gray mustache twirled at the ends, readily admitted he holds true to the stereotype of the fiery Italian. But not all his recollections are maudlin when it comes to the dog.

The story of Jimmy De Pierro and Mr. Cheeseface began in the summer of 1969. De Pierro was traveling the country with his then-girlfriend, Betty, whom he called "the great love of my life." Watching him drift into one glassy-eyed memory of Mr. Cheeseface after another, an observer might conclude that the mutt ranked an extremely close second.

The freewheeling couple was traveling the country in a 1954 Ford panel truck converted into a camper. De Pierro said they were looking for a place to call home, sampling various locations. Eventually, they landed at a friend's house in Berkeley, Calif., the freaky epicenter of '60s counterculture. There, recalled De Pierro, as he was lighting up joints one afternoon in a room full of hippies, Mr. Cheeseface wandered into his life.

"This little black-and-white puppy came into the room, and I fell in love right away," said De Pierro. "I knew from the get-go that this dog was something. He had personality up the ass."

Puppies generally have plenty of personality. But Mr. Cheeseface may have had reason to display more than most.

"It was rumored he was probably dosed," explained De Pierro.

The pup, then only a few months old, belonged to one of several young women who lived in the communal house. He "was basically a free-range dog," related De Pierro. "He had free rein, and he would roam the neighborhood with all these acid freaks."

Had the dog really been slipped hallucinogens? "I'm not saying he was," said De Pierro, "but it was a possibility."

Either way, De Pierro fell hard. He and Betty convinced the pup's owner to let them have him when they headed back to the East Coast.

"We were in love with the dog and decided he was coming with us no matter what," De Pierro said.

For a time, the dog went by his original given name, Chiisai — the Japanese word for "small." The dog's first owner believed the word meant "little friend." And, instead of pronouncing it correctly as "chee-SIGH," she went with "chee-SAY." This would become important.

One Sunday afternoon on the way back east, De Pierro craved a big Italian dinner like the ones he used to have as a kid in New York. He and Betty stopped at a restaurant just outside Chicago and left the puppy in the truck.

When they returned and opened the door of the vehicle, they found him with his face covered in cheese, a mangled bag of Locatelli beside him.

"And I said, 'Why, you fuckin' cheese-face motherfucker!'" De Pierro remembered. "'From now on, I'm calling you Cheeseface!'"

And so, because a hippie in Berkeley mispronounced a Japanese word, Chiisai was Cheeseface — rather, Mr. Cheeseface — forevermore.

"It sounded so close, he never even noticed," said De Pierro.

A Star Is Born

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Mark De Pierro

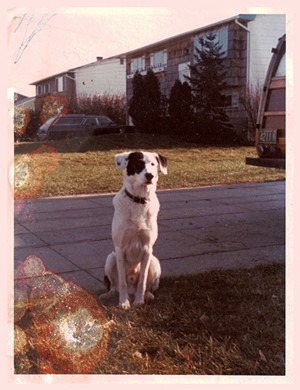

- Mr. Cheeseface

If this were the movie that De Pierro wishes National Lampoon would make about Mr. Cheeseface, now would be the time for the whimsical montage. We'd see De Pierro — skinny, hairy and smiling — strutting down a New York City street in the springtime with an adolescent Mr. Cheeseface padding to and fro a few yards ahead — off leash, of course. There'd be scenes of frolicking in a city park, going for drives in the country and, eventually, De Pierro, Betty and Mr. Cheeseface romping on a rolling spread in rural Vermont. Ideally, the whole thing would be set to era-appropriate music with just the right balance of sweet and cheesy — say, Bobby Goldsboro's 1970 hit "Watching Scotty Grow."

Toward the end, though, the montage would turn sad. We'd see De Pierro and Betty arguing loudly in a cabin while a dejected Mr. Cheeseface lay on the porch, head on paws. De Pierro would storm out the front door and hop in a van. Mr. Cheeseface would stand and gaze at the van, then back at the front door of the cabin. After a moment of contemplation, he'd bound off the porch and into the passenger seat just before De Pierro tore off in a cloud of dust, leaving for good.

The next time we see them, De Pierro and Mr. Cheeseface would be on a New York City street at a door that read Coleman Younger Motorcycle Messenger & Trucking Co. De Pierro, clutching rolled-up newspaper employment ads, would open the door as Mr. Cheeseface trailed behind.

"I was probably the fastest guy in New York," said De Pierro of his career as a courier. He worked for the messenger service on and off for several years, often splitting time between the city and a back-to-the-landers' commune in Island Pond. Wherever he went, Mr. Cheeseface did, too. That included delivering messages — a team-up that, according to De Pierro, was born as much from practicality as from companionship.

"In those days, they couldn't tow a vehicle with a dog in it," he explained. "So his job was to sit in the van while I made deliveries."

One day in 1972, De Pierro picked up a bunch of envelopes all addressed to various NYC animal talent agencies.

"The first commandment is, you don't fuck with the messages," said De Pierro. But on this occasion he couldn't resist, especially with Mr. Cheeseface riding shotgun. Committing the cardinal sin of messengers, he opened the envelopes. They were filled with head shots of dogs.

"I said, 'Mr. Cheeseface has got it on these guys,'" De Pierro recalled. From then on, every time he made a delivery to an animal talent agency, he talked up Mr. Cheeseface. His pitch finally landed at All Tame Animals, which lined up Mr. Cheeseface's gig at the then-fledgling National Lampoon as the cover dog for the Death issue. That photo shoot is depicted in the 2018 Netflix movie A Futile and Stupid Gesture, which is based on Karp's book.

How the shoot went down, and specifically how photographer Ronald G. Harris captured the dog's famous expression, is the subject of some debate. According to an email Harris sent to writer Siobhan O'Shea following her 2017 article on Mr. Cheeseface for the website Interesly, Harris, art director Gross and others at the photographer's Chelsea studio tried everything they could to get the dog's attention. But Mr. Cheeseface, who was not a trained performer by any stretch, wouldn't cooperate. According to Harris, only when the hand model pulled the unloaded gun's trigger did the dog react.

De Pierro remembers the photo shoot differently. He said Harris had a large bulldog with him in the studio that drew Mr. Cheeseface's undivided attention.

"Cheeseface was a scrapper," De Pierro explained. "He never lost a fight in his life, but he also knew which dogs to fight. He took one look at that bulldog, and he didn't want any piece of him."

De Pierro said the click of the empty revolver didn't faze Cheeseface. Rather, he argued, the nose of the gun brushed the dog's ear as the hand model moved closer and closer, and the contact is what diverted Mr. Cheeseface's attention from the bulldog.

That might seem like an irrelevant and nitpicky distinction. But to De Pierro, it's important.

He said Mr. Cheeseface feared only one thing: loud noises — booms, specifically. By way of example, De Pierro recalled a night years later when he and the dog were camping on an observation tower in the Adirondacks and a severe thunderstorm blew through. Mr. Cheeseface was so terrified, De Pierro said, that the only way he could get the 75-pound dog down from the tower was to haul him down the stairs in an oversize duffel bag.

Many dogs are afraid of thunder. But De Pierro believes Mr. Cheeseface's fear was something deeper: a premonition.

"I think he knew what was going to happen to him," De Pierro said gravely. "I think he knew he was gonna get shot."

Kingdom Come

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Mark De Pierro

- The puppies

Mr. Cheeseface's modeling career was short-lived. He appeared in just one other print ad, for a talking Frigidaire refrigerator. By the summer of 1976, the dog, De Pierro and Daye were living in East Charleston, Vt. The couple had bought a house for $4,000 on 10 Mile Square Road and were awaiting the birth of their first child, James. But when he arrived that July, the baby wasn't the only offspring in the family's Northeast Kingdom home.

The previous year, the couple had lived in rural Pennsylvania, where Mr. Cheeseface — known to sow his wild oats — had sired a litter of eight puppies with a Saint Bernard named Bertha. Four of the pups, which the De Pierros adopted and brought to Vermont, were black and white like their father. There were three males — dubbed St. Meathead, Bonehead and Twoface — and a female, Flopface. (Clearly, De Pierro has a flair for dog names.)

Flopface ran off shortly after the family moved to East Charleston and was never seen again. Then, a couple of weeks after De Pierro's son was born, Mr. Cheeseface disappeared, too.

De Pierro generally allowed Mr. Cheeseface to come and go as he pleased, and it wasn't unusual for the dog to wander off, so no one was concerned at first. De Pierro suspected Mr. Cheeseface had taken up with a neighbor's female dog, a German shepherd that was in heat. He'd also noticed a change in his furry companion since his son was born.

"He didn't like it one bit," said De Pierro of the dog's reaction to the newborn. "I knew I would probably have to do something about the dog eventually."

After two weeks, Mr. Cheeseface still hadn't returned. Then Twoface went missing.

Soon after, Twoface was found nearby, shot to death. So was the corpse of another dog that had been dead even longer. Sometime later, Bonehead was found at the Barton dump, also shot. The culprit was widely believed to be a local hunter who had been shooting dogs in the area, claiming they'd been chasing deer.

"He was going down the road shooting every dog along 10 Mile Square Road," De Pierro recalled.

It's illegal to allow dogs to chase deer and moose in Vermont, because a dog will chase a deer until the wild animal drops dead. According to 10 V.S.A. 4748, officials are authorized to shoot any dog engaged in such a pursuit on sight.

Civilians do not have that authority. But, back then in the Northeast Kingdom, it wasn't uncommon for hunters to put down dogs they believed to be running deer.

"Everyone knew that's what happened when you let your dogs run free," said Mary Sue McCarthy. She and her late husband, Michael McCarthy, were neighbors of the De Pierros in 1976. Their dog was also among those shot that summer.

One evening in early August, De Pierro was drinking whiskey with Michael McCarthy at the latter's home when they heard a shot.

"I said, 'Son of a bitch, that fuckin' dog shooter is out there again,'" De Pierro recalled. He jumped on his bicycle and pedaled like mad for home. He found Kathy holding James on the lawn beside a bloodied St. Meathead. The dog would live, but he was badly wounded in the shoulder.

Enraged, De Pierro sped off down the road on his bicycle hoping to catch the shooter, who had begun to drive away in a truck. To both his and Kathy's surprise, the driver stopped.

"He stopped so that he could tell you that he had shot Cheeseface, too," said Daye.

"He said, 'I can show you the graves of the deer your dogs have been killing,'" said De Pierro. "I said, 'You'd better get a shovel and start digging your own grave.'"

Who Shot Mr. Cheeseface?

click to enlarge

- Courtesy Of Mark De Pierro

De Pierro never made good on that hot-blooded threat. But he did write an open letter titled "Beware the Man That Murders Our Dogs — An Open Letter to the Good People of Charleston, Brighton, Morgan, Holland, and Surrounding Areas, a Very True Story." In it, he accused a neighbor of shooting his and other dogs. De Pierro had copies of the letter made and distributed them throughout the area. Then, fearing for their safety, he and Daye packed up their baby and left to live with De Pierro's parents on Long Island. They returned to Vermont in 1981.

De Pierro refused to name the shooter and repeatedly insisted that Seven Days not reveal his identity. However, Seven Days uncovered a November 1976 civil lawsuit he and Daye had filed against a Charleston resident named David Bradshaw.

In the suit, the De Pierros alleged that Bradshaw shot Mr. Cheeseface, Twoface and St. Meathead "without legal authority." Claiming emotional distress, the couple sought damages in the amount of $25,000 each for Mr. Cheeseface and Twoface, as well as $1,000 for St. Meathead — plus $27 to cover the latter's veterinarian bill. Since Mr. Cheeseface had value as a model, they sought an additional $10,000 in damages.

According to court filings, Bradshaw denied the allegations and filed a counterclaim seeking $100,000 in total damages. He alleged that De Pierro's open letter was libelous and defamatory, and that as a result of its publication he had been "held up to public scorn and contempt, has suffered greatly in body and mind, has been injured in his livelihood and has been injured and damaged emotionally." The case was eventually dismissed.

Bradshaw, now 74, did not respond to Seven Days' multiple attempts to contact him. Publicly available information reveals him, however, to be an interesting character.

Bradshaw is a visual artist of some renown who has worked with, among others, Texas sculptor James Surls, New York abstract artist Philip Taaffe and painter Robert Rauschenberg. A close friend and collaborator of William S. Burroughs, he served as a pallbearer at the writer's funeral in 1997.

Bradshaw is also a competitive marksman. While he originally became known for his abstract paintings, his most famous, or perhaps infamous, pieces combine his passions for art and firearms. In a 2003 profile for New Orleans' Times-Picayune, art critic Doug MacCash described Bradshaw's work.

"Instead of using a brush and palette, he paints with assault rifles and custom-made pistols," wrote MacCash. "There are torso-shaped iron plates, so pocked with bullet dents that they curl at the edges like potato chips. Cardboard targets, coarsely painted with the silhouettes of animals, are riddled with holes, repaired with squares of brown tape and riddled again. Paper targets are pierced with tightly clustered holes and signed as if they were an edition of prints."

While that description might trigger suspicion of Bradshaw as the shooter, none of it is precisely an indictment of the man.

De Pierro recalled that Mary Sue McCarthy helped make copies of his infamous 1976 open letter.

McCarthy, however, has no recollection of either the letter or making copies of it. "I barely remember what happened yesterday," she said, adding that she bore whoever shot her dog no ill will. "It was 40 years ago. People did things differently then."

Bill Thompson of Island Pond was another neighbor of the De Pierros' in 1976.

"I have no idea who did it," said Thompson. "I remember Cheeseface was killed by a hunter because he was running deer. We all knew that hunters shoot dogs that run deer, so it wasn't really surprising. But it was heartbreaking, for Jimmy especially.

"But that's the law up here," he continued, describing the Northeast Kingdom of the 1970s as akin to the Wild West. "Back then, everybody wore guns on their hips."

"I can't say he wasn't running deer," admitted De Pierro of Mr. Cheeseface. But he still believes the dog wasn't motivated by an urge to stalk wildlife. "The chances are that he was looking for the German shepherd bitch in heat," he said. "He was looking for love."

De Pierro doesn't believe any of Mr. Cheeseface's offspring, barely a year old at the time, were running deer, either.

"They were puppies," he said. "They looked big because they were part Saint Bernard. But they were puppies."

A strong believer in fate, De Pierro thinks he ultimately ended up with the right dog for his young family: St. Meathead. The gentle Saint Bernard mix was part of the De Pierro clan until his death, of natural causes, in 1984.

"I would have had to do something about Mr. Cheeseface before long," said De Pierro. "Meathead was the dog we were meant to have."

As for the shooter, De Pierro wishes no harm to him and hopes for a civil resolution one day.

"I would like to sit down with him and make peace," De Pierro said.

Buy This Magazine Or The Dog Gets It

Source: https://www.sevendaysvt.com/vermont/who-shot-mr-cheeseface-the-vermont-demise-of-a-famous-mutt/Content?oid=23671435

Posted by: oldhamcopievere.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Buy This Magazine Or The Dog Gets It"

Post a Comment